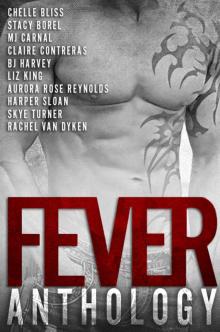

Fever Read online

Copyright © 2005 by Sean Rowe

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com.

First eBook Edition: September 2005

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN 978-0-316-02820-2

Contents

DEDICATION

PART ONE: FIRE

CHAPTER: 1

CHAPTER: 2

CHAPTER: 3

CHAPTER: 4

CHAPTER: 5

CHAPTER: 6

PART TWO: WATER

CHAPTER: 7

CHAPTER: 8

CHAPTER: 9

CHAPTER: 10

CHAPTER: 11

CHAPTER: 12

CHAPTER: 13

CHAPTER: 14

CHAPTER: 15

CHAPTER: 16

CHAPTER: 17

CHAPTER: 18

PART THREE: SNOW

CHAPTER: 19

CHAPTER: 20

CHAPTER: 21

CHAPTER: 22

CHAPTER: 23

CHAPTER: 24

CHAPTER: 25

CHAPTER: 26

CHAPTER: 27

CHAPTER: 28

CHAPTER: 29

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

for

Tom & Jan

PART ONE

FIRE

1

SOME GUYS DON’T KNOW when to quit. That’s your problem.”

It was Fontana’s voice. I heard the voice before I felt the hand on my shoulder. When I looked up he was standing behind me, hazy in the smoked glass of the mirror on the back bar, out of prison three years early.

“You think you’ve seen it all,” he said, the hand gone. “You think you’ve run your course, but you can’t quite bring yourself to cash it in. So on you go: another day, another drink. What you really need is to find some noble exit. Some way of going out in a big blaze of glory.”

The kid behind the bar had been filling sample glasses and letting me taste each one. The place made its own beer: raspberry, India pale ale, one that tasted like molasses. You could see big copper vats behind a glass wall.

“Let’s grab a table outside,” Fontana said. “You have to get out in the sun, or what’s the point? This is Miami.”

When I got up he was already walking out to the patio, wind catching his jacket. I couldn’t see if he was carrying.

“Check it out,” he said when we were sitting down.

I thought he meant the girl on the Jet Ski, but he was looking at a rust-bucket freighter coming toward us down Government Cut. The harbor pilot went on ahead. A tug stayed behind the pilot boat, slaloming through the chop, dragging the freighter backward out the ship channel.

Fontana put on a pair of sunglasses. He had binoculars with him: civilian ones, out of a sporting goods store.

“You could drop that baby in the mouth of the channel and shut down this whole city for a week,” he said, looking at the freighter. “Three days, anyway. The cargo port. The river. Half the cruise ships in North America.”

I didn’t know if we were bumping into each other or it was something else. He picked up the field glasses, and I caught a flash of holster leather underneath his jacket.

“You’d have to make sure it swung sideways,” I offered. “Before you blew it.”

“Or after.” He put down the binoculars. “How you liking retirement, Matthew? Or I guess it’s semiretirement?”

“Fine. Same as you, right?”

“I don’t think so. Anyway, that’s not what I hear.”

“No?”

The freighter was passing us now, about sixty yards from the patio. A woman at a table nearby was showing a little boy how to wave. There was a man on the freighter’s bridge in a white shirt with blue epaulettes on the shoulders. The man dragged on a cigarette. I got one out myself.

“So you’re living down here again?”

“It’s a great town,” he replied, not exactly an answer.

I looked at him the way you do with people, trying to get a good, full look when you think they won’t catch you doing it. He was thinner, and I could understand why he wanted to be outside: he was very pale. I noticed caps on a couple of teeth.

“How long you been out?”

“Three weeks and three days,” he said, taking off his sunglasses and cleaning them with a napkin.

“How was it?”

He blew on his glasses and kept rubbing. “How was it? That’s a great question, Matt. Well, let me see: how was it. Do you know what a blanket party is?”

“I’ve heard the term. What do you say we just drop it?”

“They bring you down the cell block the first day, all the way down and back up the other side, their version of a perp walk. Then they open the door of a holding cell and in you go. All the cons are waiting to meet you. It’s the neighborhood welcoming committee. A couple guys stand up, taking their time. They hold a blanket in front of the bars, and the next thing you know, another one of ’em gets around behind you and hits you with something sneaky, maybe a soup can stuck in a sock. You go down, and that’s when the fun begins. They take turns with you, Matt, that’s what they do, three or four guys holding you down with a towel stuck in your mouth, everyone else helping out and taking turns. That’s a blanket party.”

He finished with his glasses and put them back on. “I’m trying to think what else I can tell you about being a defrocked drug agent in a state penitentiary. I caught up on my knitting?”

“I’m going to order a drink,” I said, and I did. I thought about the bottle of Advil in my desk drawer at work. My hand ached, worse than it had in weeks.

“One hell of a current in there at the change of tide,” Fontana was saying. “Especially an autumn tide. Mix it up with a new moon, you got a doozy. That’s why that tug’s straining like it is.”

I looked, and he was right.

“The way to do it is wait till the freighter’s right between the jetties, the narrowest point. You do it with some dynamite in the bow, say fifteen pounds. Nothing fancy. Dynamite and sandbags, a directed charge. You blow a hole in the port bow; it swings the whole ship around. Kid stuff.”

“You need a hobby.”

He laughed. “What I hear is you like to drink a fifth of Maker’s Mark a day and hang out in titty bars. Is that a hobby?”

I shrugged. “It’s a free country.”

“Yeah? You should turn on CNN sometime. You got survivalist militias, you got whacked-out religious cults, you got kids with purple hair running around calling themselves antiglobalists. They don’t think it’s a free country. The whole thing makes me glad I’m out of law enforcement. Maybe you should get out too.”

He couldn’t leave the binoculars alone. He had picked them up again, taking off his glasses to squint through them. He said, “You could get some serious action in this town, come to think of it. Your old buddies at the Bureau are scared shitless these Cubans are going to get serious someday, actually do something instead of screaming at each other on AM radio and shaking their fists at Castro.”

“I wouldn’t know.”

“I thought you out-to-pasture FBI guys all stayed in touch, had cocktail parties.”

I let it slide. It was a nice afternoon, cool for October and a little windy. Fishing boats were scatte

red all over the channel, a regular traffic jam. I felt sorry for the harbor pilot. Not too sorry, of course; those guys have a hell of a union. I could see the stern of the freighter now. In a few minutes the ship would be heading out to sea. The waitress brought my drink.

“I been playing with this thing,” Fontana said. He had slipped on a pair of calfskin gloves. I looked down, and there was a little black gizmo on the table. “Try it out. You’ll get addicted. A friend of mine, his sister’s kid turned me on to it.”

There was a screen, like on a pager. The thing was the size of a cigarette pack, with a dull metal casing, and when I picked it up, it was heavier than I had thought it would be. I wasn’t big on games.

“You push the button on the side to start it up,” he said.

I did. Nothing happened. Then the screen lit up and displayed little green letters. The little green letters said, Bang!

Right then I knew what was going to happen next but I didn’t even have time to breathe.

The explosion ripped through the patio like a gust of wind. Someone in one of the fishing boats was yelling, “¡Coño! ¡Coño! ¡Coño!” Everyone was screaming. On the wooden deck, on my stomach, I looked out from between two balusters and saw the freighter in flames. It had swung sideways in the channel, nose down and sinking fast. A guy on the tugboat was going nuts, trying to get the lines loose. He gave up and dove overboard, and the tug capsized.

Fontana was still sitting in his chair. He was laughing, sipping my drink. “This is great,” he said. He got up, giving his jacket a little hitch.

“You owe me one,” he added, “and this is it, some of it, anyway. Let’s not forget who could have been sitting in that eight-by-twelve up at Raiford the last three years instead of me. I’m at the Delano. You feel like it, give me a call. I got something going on I’d like to include you in.”

He gave the gizmo a glance. It was under the table next to my foot, or had been; now I didn’t see it. “You know, Matthew, a man can go his whole life in this country and never know if he’s a coward. You want a blaze of glory? I’m going to serve it to you on a silver fucking platter.”

He laughed again and walked inside. No one paid attention to him. After another minute I got up and sat in the chair and finished my drink, thinking to slip the black box in my pocket.

I reached down for it and froze. I shoved the table aside. The deck underneath was empty.

“The Vanishing Jack” was Fontana’s favorite card trick from years ago. He would do it so fast you hardly saw his hands move.

2

THE NEXT MORNING it was all over the front page of the Herald. Hector came in around eight thirty, sat with one leg over the chair arm in my office, and read the whole thing out loud. Especially the letter.

The letter called Castro the Antichrist and also had some choice words for Congress, for gutting the travel embargo. The idea was that Cuban hard-liners in Miami had blown up the freighter as a warning. Bigger trouble was promised if the United States didn’t do some soul-searching and reimpose full trade sanctions against Havana, cut off diplomatic ties, make the ballet dancers and boxers stay home. An exile’s pipe dream.

And that’s what made the letter perfect: the delusion. It hit every note, right down to the spelling mistakes. It was signed the October 28th Brigade. Today was Thursday, October 29.

“What do you think?” Hector asked. The kid was playing it cool.

“I think someone better get the channel open or we’re both out of a job.”

The Corps of Engineers had a two-thousand-ton barge crane on its way down from Titusville. Meanwhile thirty freighters were backed up in Lagarre Anchorage off Miami Beach, waiting to get into port. The inbound cruise ships were being diverted to Port Everglades and Port Canaveral, but the larger problem was the six luxury liners trapped in their berths at Dodge Island, each one bigger than a football field. The Italians at Costa Cruises had already tried to run the Majesty of the Waves through Cape Florida Channel and gone aground.

At noon I was going to meet at the port director’s office with people from the three top cruise lines. Tanel, the big man in our outfit, was flying in from Chicago with a couple of board members, and right now I wanted to get rid of Hector. On the other hand, he was a good weather vane.

“What do you think?” I asked.

He shrugged. “It could be a hoax. It could be an insurance scam, or some kind of business payback. The freighter was docked on the river. Those guys on the river are animals. It’s a fight to the death up there.”

“But you don’t think so.”

“No,” he said, heating up. “This thing with Cuba, there had to be some kind of backlash. I mean, it’s the final betrayal, right? You start with Kennedy and the Bay of Pigs and end up with Congress queering the Helms-Burton Act. There was a rumor downtown a couple of days ago that Castro was getting invited to the White House for dinner.”

Another pipe dream. I wondered if Hector believed it or if he was just bringing it up as a sample of local gossip.

“Oh boy.” I acted like I’d thought of something. “I need you to take Neal and do a walk-through on the Ecstasy. Not the passenger areas, just the chandler bays. Look for anything out of the ordinary. New trucks, people you don’t recognize. Get the purser to go over the provisions manifest. Tell him I said so.”

“OK, chief. You want me to leave the newspaper?”

Hector called me “chief” whenever he got excited. The last time was in June after one of the cabin stewards raped a passenger on the Stargazer. I had a sudden image of Hector and Neal Atlee beating him with chopped-off pool cues behind a stack of ship containers, the floodlights from the gantries shining down on wet asphalt. Afterward, we put the steward on a plane back to Malaysia. The company settled out of court with the girl’s parents, which was routine, but this time the price tag was high six figures. Things had been pretty quiet since Labor Day.

I told Hector to take his paper with him, and I tried to get ready for the meeting. Dolores brought in a list of employees hired in the last three months. The officers were all Svens and Larses. The crew was mostly Filipino, some South Americans. While I went through the list I called Paul Lewis at the North Miami field office, expecting to get his voice mail. He picked up and said, “Well, well. Loose Cannon Shannon.”

“Paul. I hate to trouble you, but I’ve got a sit-down in three hours with the port director and Tanel and the whole Supreme Soviet down here.”

“I know. I’m invited.”

“I wasn’t aware.”

“I’m supposed to assure you guys that the FBI has a serious hard-on for the bomber. Which we do. The way I know is I’ve got nine agents on loan from Atlanta camped out in the bull pen. None of them speak any Spanish, of course. I’m going to say your people are supposed to keep their eyes peeled for suspicious characters, like guys carrying Cuban flags and tote bags full of dynamite.”

I decided not to ask about the dynamite. Then I wondered. The newspaper hadn’t said a word about dynamite. It was a detail that had been held back from the press. So why would Lewis mention it? It was exactly the kind of thing I would have thrown out as bait, just to see who nibbled. Or who didn’t. But now it was too late to bite.

“You think this is for real?”

“It doesn’t matter what I think,” he said. “The lab has the letter that was sent to the Herald, I’m not telling you anything you wouldn’t know anyway. Maybe forensics in Washington can do something with it. Meanwhile we beat the bushes.”

“They’re going to want me to run my own investigation. I can smell it coming.”

Lewis laughed. “Not a good idea.”

“I know. I was thinking you could mention that to Tanel.”

“I’m getting the picture,” he said. “By the way, how much they paying you over there, Matt?”

“A lot,” I said, lying. “You’re coming up on your twenty-five, aren’t you?”

“You got that right.”

“What’s y

our plan?”

“Go somewhere with trout and forget I met the human race. I’ve got to run. See you at noon.”

TANEL MADE A STEEPLE out of his fingers and said, “I think at this juncture we’d all like to hear from our director of security.”

The eyes swung my way, the chairs squeaking. Tanel was Israeli, but he was going through a big English-gentleman phase. All the chairs were burgundy leather. I expected pictures of fox hunts on the walls any day now. The English-gentleman phase included Mary, and Tanel was in the bad habit of bringing her to meetings to serve drinks. Today she wore slacks that were like riding pants, and a tweed jacket. She set a glass of Scotch in front of Tanel. The rest of us were drinking coffee or fizz water. I had to hand it to the old guy, he didn’t give a shit. One in the afternoon, and he was on his third double.

“I’ll start with what we know,” I began. “We’ve got a hundred-and-ninety-foot bulk cargo trader owned by Poseidon Transport sunk at the mouth of the ship channel. It’ll be up and out in seventy-two hours, maybe sooner. Until then we’ve got a logistical —”

“Nightmare,” said Tanel. “You can go ahead and say it, Matt.”

A little joke from the big man. He was looking at the ceiling now, swiveled back from the conference table with his fingers laced behind his neck.

“Right,” I said. “Some real challenges.”

“We already know that. Do you think this is terrorism?”

“I don’t know. In a sense it’s irrelevant. The thing to do at this stage is take precautions, which we’re doing.” I wanted to back up a little. I waited to see if I had the floor. “We’ve got a blown-up freighter and a letter in the Herald that may or may not be authentic. Let’s keep in mind there’s been no loss of life.”

“But that’s just by happenstance, now isn’t it?”

Tanel again, the debate team captain.

“Hard to say.”

This time I gave it a good long pause, to be sure I had settled his hash. I was planning to touch on the cancellations the marketing guy had just gone over, maybe repackage some of Paul Lewis’s speech. Lewis had left ten minutes earlier with the Italians and the people from Trinity, the number two line. It was just the big boys now and the port director and some of his staff. Fuck it, I thought, here we go.

Fever

Fever